On November 25

“There was a husband who asked much and gave much, and out of the giving and the asking wove with a woman what could not be broken in life, and in a moment it was no more. And so she took a ring from her finger and placed it in his hands, and kissed him and closed the lid of a coffin.”

~Mike Mansfield

Majority Leader of the United States Senate

John F. Kennedy Eulogy

=======================

=======================

1839 – A cyclone slammed India with high winds and a 40 foot storm surge.

It destroyed the port city of Coringa (never to be entirely rebuilt again). The storm wave swept inland, taking with it 20,000 ships and thousands of people.

An estimated 300,000 deaths resulted from the disaster.

1864 – A group of Confederate operatives calling themselves the Confederate Army of Manhattan, started fires in more than 20 locations in an unsuccessful attempt to burn down New York City.

Their weapons of choice were 144 small vials of “Greek Fire,” a special chemical combination that looked like water but when exposed to air, would, after a short delay, ignite in flames.

Most of the fires fizzled out on their own or failed to ignite completely. The Confederates forgot to open the windows in any of the rooms, which robbed the flames of a steady supply of oxygen.

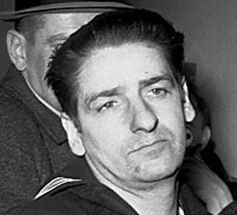

All the operatives escaped prosecution except for Robert Cobb Kennedy (shown above), who was apprehended in January 1865 while trying to travel from Canada to Richmond, VA.

He was tried, convicted, and executed on March 25, 1865, at Fort Lafayette in New York harbor.

1876 – U.S. troops under the command of General Ranald Mackenzie destroyed a village of Cheyenne Indians in central Wyoming during an incident known as Dull Knife Fight or Red Fork Battle.

The attack was in retaliation against some of the Indians who had participated in the massacre of Custer and his men at Little Bighorn exactly five months earlier.

At dawn, Mackenzie and over 1,000 soldiers and 400 Indian scouts opened fire on the sleeping village, killing many Indians within the first few minutes.

Some of the Cheyenne managed to run into the surrounding hills where they watched as the soldiers burned more than 200 lodges-containing all their winter food and clothing.

1940 – Woody Woodpecker made his first appearance in the cartoon, Knock Knock.

The idea for Woody came during producer Walter Lantz’s honeymoon with wife, Gracie, in Sherwood Lake, CA. A noisy woodpecker outside their cabin kept the couple awake at night, and when a heavy rain started, they learned that the bird had bored holes in their cabin’s roof.

Lantz wanted to shoot the bird, but Gracie suggested that her husband make a cartoon about him.

1941 – British battleship HMS Barham was sunk by a German submarine.

The torpedoes were fired from a range of only 750 yards providing no time for evasive action. As the Barham rolled over to port, her magazines of ammo exploded and she quickly sank.

The explosion was caught by cameraman John Turner, who was on the deck of a nearby ship.

Out of a crew of approximately 1,184 officers and men, 841 were killed.

1944 – A German V-2 rocket hit the roof of a Woolworth’s store in Deptford, London, England.

The Royal Arsenal Co-operative Society Store next door and a line of people waiting for a tram in the street outside were caught in the inferno.

A total of 168 people died.

1949 – Bill “Bojangles” Robinson died of heart failure at the age of 71.

He was a tap dancer extraordinaire and an actor best known for his films with a very young Shirley Temple (The Little Colonel, The Littlest Rebel, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm).

1963 – Three days after his assassination in Dallas, Texas, President John F. Kennedy was laid to rest with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

Hundreds of thousands of people lined the streets of Washington to watch a horse-drawn caisson bear Kennedy’s body from the Capitol Rotunda to St. Matthew’s Catholic Cathedral for a requiem Mass.

The solemn procession then continued on to Arlington National Cemetery, where leaders of 99 nations gathered for the state funeral.

Kennedy was buried on a slope below Arlington House, where an eternal flame was lit by his widow to forever mark the grave.

1963 – Hours after President John Kennedy was buried, Lee Harvey Oswald – his alleged killer – was buried in Shannon Rose Hill Memorial Burial Park in Fort Worth.

Dozens of police, federal agents and members of the press were present but there were no mourners, other than Oswald’s family: mother Marguerite, brother Robert, widow Marina and her two daughters, June Lee, 2, and infant Rachel.

With no mourners present to act as pallbearers, it was left to members of the media to carry Oswald’s casket to his grave.

1963 – There was a third funeral that day.

Police officer J.D. Tippit, an 11-year veteran with the Dallas Police Department who had allegedly been gunned down by Lee Harvey Oswald approximately 45 minutes after President Kennedy was shot, was buried at Laurel Land Memorial Park in Dallas.

1969 – John Lennon returned his Member of the British Empire medal to protest Britain’s involvement in Biafra and Vietnam.

In a playful aside – which actually cheapened his protest – he added he was also upset his latest single (Cold Turkey) was slipping down the charts.

Lennon later said he’d never wanted the MBE when the Beatles received theirs in 1965 but just went along with it.

“It all just seemed part of the game we’d agreed to play. We had nothing to lose, except that bit of you that said you didn’t believe in it.”

1973 – Actor Laurence Harvey died from stomach cancer at the age of 45.

He starred in The Alamo, The Manchurian Candidate, and Room At The Top, which earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor.

1973 – Albert DeSalvo, who confessed to being the Boston Strangler, the murderer of thirteen women in the Boston area in the 1960s, was found stabbed to death in the Walpole State Prison infirmary.

Robert Wilson, a fellow inmate, was tried for DeSalvo’s murder but the trial ended in a hung jury. No one was ever convicted for his murder. The case remains unsolved.

DeSalvo, who was serving a life sentence, was never imprisoned for the murders, but rather for a series of rapes.

His murder confessions – which he later recanted – have been disputed and debate continues as to which crimes DeSalvo actually committed.

1976 – At the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco, The Band played their last concert, which was filmed by Martin Scorsese and released as the classic concert movie The Last Waltz.

Guest performers included Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan, Neil Diamond, Van Morrison, Neil Young, and the Staples Singers.

1979 – Pat Summerall and John Madden called an NFL game on CBS for the first time.

They would go on to work together for 22 years and become one of the most well-known partnerships in TV sportscasting history.

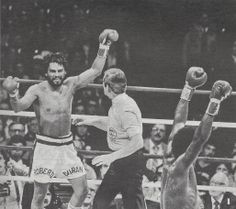

1980 – Sugar Ray Leonard regained boxing’s welterweight title when his opponent, reigning champ Roberto Duran, waved his arms and walked away from the fight in the eighth round. “No más, no más,”

Duran told the referee. “No more box.” He’d had cramps in his stomach since the fifth round, he said, and they’d gotten so bad he could barely stand up.

1981 – Actor Jack Albertson died of cancer at the age of 74.

He starred in Man Of A Thousand Faces, Kissin’ Cousins, The Poseidon Adventure, Willie Wonka & The Chocolate Factory, The Subject Was Roses {for which he earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor}, and of course, television’s Chico And The Man.

1984 – Thirty-six legendary British rock musicians set aside their egos and grouped together to raise funds for Ethiopian famine relief.

Calling themselves Band Aid, they recorded the charity single Do They Know It’s Christmas? at Sarm West Studios in London.

The song – co-written by Bob Geldof and Midge Ure – is the second highest selling single in UK chart history.

Geldof and Ure later co-organized the Live Aid and Live 8 charity concerts.

“It was a song written for a specific purpose: to touch people’s heartstrings and to loosen the purse strings. We were looking at television pictures of children spending five minutes just trying to stand up.”

~Midge Ure

1986 – Three weeks after a Lebanese magazine reported that the United States had been secretly selling arms to Iran, Attorney General Edwin Meese revealed that proceeds from the arms sales were illegally diverted to the anti-communist Contras in Nicaragua.

Meese announced that the arms sales proceeds were diverted to fund the Contras who were fighting a guerrilla war against the elected leftist government of Nicaragua.

The Contra connection caused outrage in Congress, which in 1982 had passed the Boland Amendment prohibiting the use of federal money “for the purpose of overthrowing the government of Nicaragua.”

The same day that the Iran-Contra connection was disclosed, President Reagan accepted the resignation of his national security adviser, Vice Admiral John Poindexter, and fired Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North, a Poindexter aide.

Both men had played key roles in the Iran-Contra operation. Reagan accepted responsibility for the arms-for-hostages deal but denied any knowledge of the diversion of funds to the Contras.

1990 – After a howling rainstorm on Thanksgiving Day, Washington state’s historic floating Lacey V. Murrow Memorial Bridge broke apart and fell to the bottom of Lake Washington, between Seattle and its suburbs to the east.

The 6,600-foot-long bridge, made of 22 floating bolted-together pontoons, was in the process of being converted from a two-way road to a one-way road.

The state highway department alleged that construction crews had left the pontoons’ hatches open, leaving them vulnerable to the weekend’s heavy rains and large waves. The construction company agreed to pay the state $20 million.

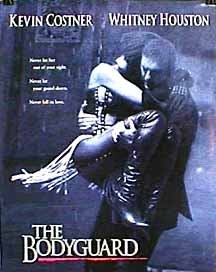

1992 – The Bodyguard, starring Kevin Costner and Whitney Houston, premiered in the U.S.

Although it would become the second highest-grossing film of 1992 (worldwide), several movie critics, Owen Gleiberman being one of them, trashed the film. Gleiberman said, “To say that Houston and Costner fail to strike sparks would be putting it mildly. It’s like watching two statues attempting to mate.”

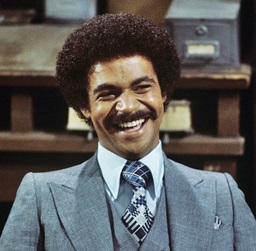

1998 – Comedian Flip Wilson died of liver cancer at the age of 64.

From 1970 to 1974, Wilson hosted his own weekly variety series, The Flip Wilson Show, and introduced viewers to his recurring character of Geraldine, a sassy liberated Southern woman who was coarsely flirty yet faithful to her boyfriend “Killer”.

The series earned Wilson a Golden Globe and two Emmy Awards, and at one point was the second highest rated show on network television.

2003 – Yemen arrested Mohammed Hamdi al-Ahdal, a top al-Qaida member suspected of masterminding the 2000 bombing of the USS Cole and the 2002 bombing of MV Limburg, a French oil tanker, off Yemen’s coast.

At his 2006 trial, al-Ahdal was never charged in the Cole or Limburg bombings. Instead, he was convicted of handling substantial funds for al Qaeda, sentenced to time already served and released.

2016 – Actor Ron Glass died of respiratory failure at the age of 71.

He was best known for his roles as literary Det. Ron Harris, who frequently seemed more preoccupied with his attire and his career as a writer than with his police work in the television sitcom Barney Miller from 1975–1982.

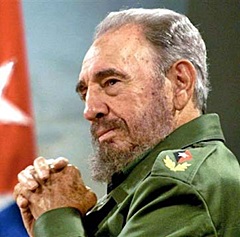

2016 – Fidel Castro died at the age of 90.

The so-called “giant of the Third World,” and a titan of the Cold War who defied 10 American presidents and thrust Cuba onto the world stage, Castro was a communist revolutionary and politician who governed the Republic of Cuba as Prime Minister from 1959 to 1976, and then as President from 1976 to 2008.

He left a very mixed legacy.

His supporters in Havana described him as a tireless defender of the poor. For five decades, his government produced tens of thousands of doctors and teachers and achieved some of the lowest infant mortality and illiteracy rates in the Western hemisphere.

However, critics say Castro drove the country into economic ruin, denied basic freedoms to 11 million Cubans at home and forced more than a million others into exile.

Compiled by Ray Lemire ©2023 RayLemire.com / Streamingoldies All Rights Reserved.